Threads of History

“the very existence of what we know as freedom”

Lake Champlain, October 1776

By John Krueger, Chair of the LCBP Heritage Area Program Advisory Committee.

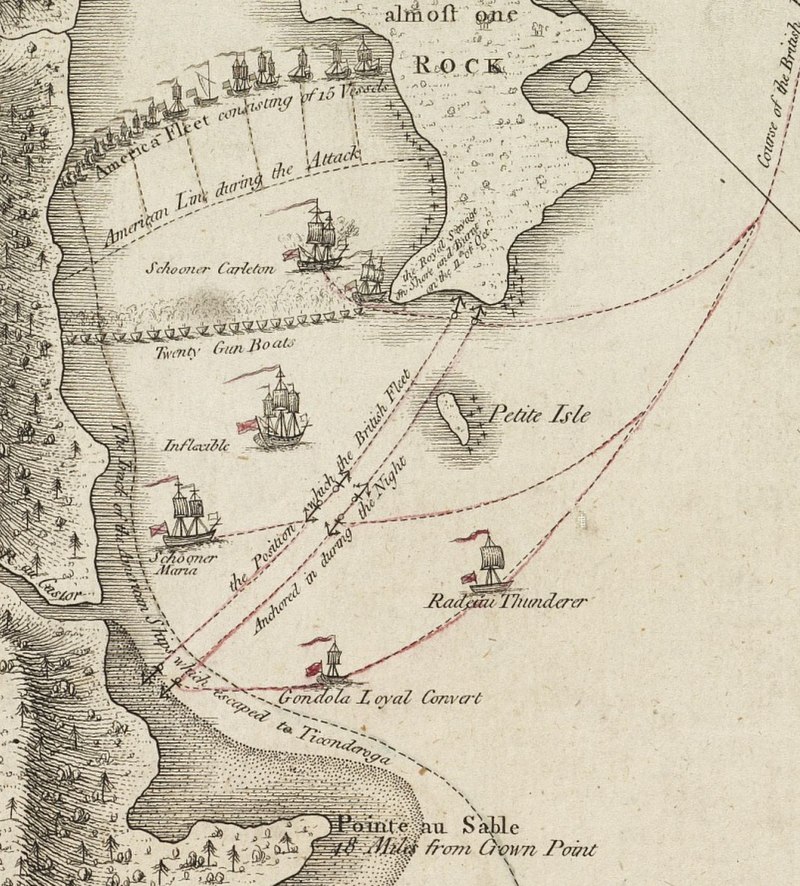

The Battle of Valcour Island. Image: National Archives of Canada

Control of Lake Champlain had become a key element in the plans of both British and American policymakers in second summer of the American War for Independence. With 13,000 British and German troops under General Sir Guy Carleton waiting to move south from Canada and a badly outnumbered army at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence serving as the rebels’ northern line of defense, naval dominance on the lake was a major goal.

The responsibility for building a fleet at Skenesborough (today’s Whitehall) went to the highly capable 35-year-old Benedict Arnold. By late summer Arnold and his captains had patched together an assortment of schooners, gunboats, and galleys, crewed largely by untrained soldiers. Working north of the border at St. Johns, General Carleton and his subordinates had assembled a more impressive flotilla crewed by experienced sailors and commanded by skilled naval officers.

After carefully reconnoitering the lake for the best anchorage, Arnold sailed his fleet into the deep channel between Valcour Island and the western shore. He believed that the over-confident British would sail south of the island before discovering the rebel vessels and then would have difficulty in beating back against the wind.

When the British squadron drew near Valcour Island on the cool, clear early morning of Friday, October 11, 1776, Royal Navy Captain Thomas Pringle ordered up the signal to engage. Arnold’s strategy forced the British ships to attack in disarray from the south. The American crews kept the fighting relatively equal at the outset, as the larger British vessels had a difficult time beating upwind to train their heavy guns on the rebel line. The American position gradually deteriorated as the day progressed.

Detail of 1776 map of Northern Lake Champlain by William Faden. Courtesy Boston Public Library.

As darkness fell, Carleton and Pringle stretched a blockade across the southern end of the channel in anticipation of accepting Arnold’s surrender in the morning. Under the cover of a heavy fog, Arnold’s captains executed a daring escape. Sailors and marines desperately sailed and rowed their battered, leaking ships to Schuyler Island, where the fleet anchored briefly to stop leaks and mend sails. When the fog lifted in the morning and Carleton discovered his quarry’s escape, a chase ensued.

On Sunday, October 13, near Split Rock, the British fleet finally caught up with the ships straggling at the rear of the American line. Arnold sailed the Congress and the four gunboats into a small bay on the lake’s eastern shore. There, just ahead of the pursuing British, he beached and burned the vessels and then led his men through the woods and across the narrows to relative safety.

Captain Peter Merrill commanded the Congress. “We didn’t know it then,” he wrote on October 12, 1776, “but on what we were doing depended the life of the Revolution, and the very existence of what we know as freedom.” The fictional Peter Merrill is a major protagonist in Rabble in Arms, the classic chronicle by Kenneth Roberts. The story of October 1776 on Lake Champlain simply cannot be told in 505 words. Read Rabble in Arms. You will not be disappointed.