Interpretive Themes

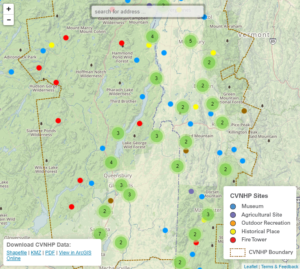

Interpretive sites throughout the CVNHP help visitors make connections between the region’s cultural and natural heritage and their own lives. Photo: LCBP

The federal legislation that authorized the CVNHP identified two key interpretive themes: Corridor of Commerce and Making of Nations. An additional theme, Conservation and Community focusing on the relationship between the people and the natural resources of the region was suggested early in the initial scoping for the CVNHP.

Making of Nations

The strategic Richelieu-Champlain-Hudson corridor was not only the setting for the well-known military campaigns and battles of the 18th and 19th centuries, it also served as an important venue for exploration and settlement, a setting for revolution and defiance, and a place of societal and governmental evolution. The early inhabitants of the region—the Mohawk, Abenaki and Mahican people—had their own history, traditions and culture long before the arrival of French explorer Samuel de Champlain in 1609.

Claimed by France to the north, the Netherlands—and later Great Britain—to the south, the strategic corridor was contested by the European powers for 150 years after Champlain’s visit. Following the British triumph in the French and Indian War in 1763, the Union Jack flew over the entire region. The Americans and British vied for control of the important corridor in the first years of the Revolutionary War. The decisive American victory at Saratoga in 1777 convinced the French that they should ally themselves with the new democracy. When the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, the British retreated into Canada, only to return during the War of 1812. Another American victory at the 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh helped secure a lasting peace between the two nations.

The young republic continued to grow in the early 1800s. The Champlain and Erie canals, along with the Chambly Canal in Quebec, made transportation infinitely easier between New York City, Canada, the Great Lakes and the American Midwest. Not just goods followed these improved trade routes, but ideas and concepts as well. Utopian societies, social movements, and new religions were created and spread from the region.

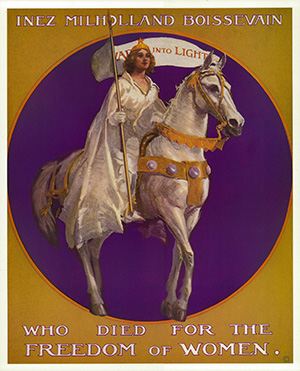

The canals and lake made the region a significant corridor of the “Underground Railroad” used by enslaved African-Americans seeking freedom in Canada. Conflict returned to the region with the la Guerre des patriotes (Patriots War) of 1837 and 1838 in the Richelieu Valley, with planning and actions staged in Vermont and New York. After the American Civil War, the Fenians—intent of pressuring Great Britain to give Ireland independence—conducted raids from the Champlain Valley into Canada.

The Irish were one of many ethnic groups that traveled and settled in the corridor. French Canadians, Welch, Italians, and others brought their languages, traditions and culture with them as they immigrated into the region and became part of its social fabric. Immigration continued over the decades with, most recently, Vietnamese, Baltic and Somali people finding refuge in the area.

The remarkable history of the CVNHP—through times of war and strife and periods of peace and prosperity—is interpreted at the many museums, historic sites and annual ethnic festivals throughout the region.

Corridor of Commerce

The geography of the Champlain and Upper Hudson River basins created a water-based trading route between the Atlantic Ocean and the St. Lawrence River long before the arrival of European explorers in the 17th century. The rich natural resources along these routes made colonization appealing, but conflict among France and English forces for control of this “water highway” made the region a dangerous place to settle. Modern commerce began in earnest after the American Revolution, and trade exploded with the opening of the Champlain Canal in 1823. Soon after, canal boats were carrying agricultural goods, stone, iron ore, and lumber to Hudson River ports and later, with the opening of the Chambly Canal, to communities along the Richelieu and St. Lawrence rivers. The canal boats returned with finished goods and coal, spurring yet more commerce.

Transportation became increasingly efficient by the mid-19th century. Railroads were carved through the rugged mountains. Along the waterways, stately steamboats carried passengers and goods the length and breadth of Lake Champlain. Many of those riding the trains and steamboats of the day were tourists escaping the stifling heat of the eastern cities and enjoying the fresh air, healing waters, and natural beauty of the region. Millions of people still visit the region every year for these very same reasons.

Conservation and Community

The earliest written accounts of agricultural activities in the CVNHP region come from Samuel de Champlain’s 1609 journal: “there were beautiful valleys in these places, with plains productive in grain, such as I had eaten in this country, together with many kinds of fruit without limit.”

Archeological evidence concurs with Champlain’s reports. Native people farmed the rich soils of the valley long before the 17th century. Early European settlers later cleared far more of the land and established farms from the Lake Champlain and Upper Hudson River to the mountain slopes, both to the east and the west, by the early 1800s. Much of this agriculture, especially in the hill country, was not sustainable and died out in response to changing economic markets by the late 19th century. Some of the practices, such as clear cutting forests followed by overgrazing, were highly detrimental to the landscape. By the late 19th century, summer vacationers and local residents began to better understand the environmental consequences of this degradation, resulting in some of the earliest environmental conservation efforts in the United States.

The conservation movement continues with a renewed public focus on air and water quality and the emergence of the “local foods” movement, with locally produced fruits, vegetables, meats, dairy and grains gaining value for not only their high-quality and nutrition, but also their environmental and economic sustainability. Browse at a small town farmers market, buy veggies at a roadside stand, or eat at a “localvore” restaurant and you might just become part of a new conservation movement!

More on Interpretation

What is Interpretation? (National Association for Interpretation) →

Foundations of Interpretation (National Park Service) →