Threads of History

“A teacher affects eternity”: Henry Adams, 1838-1918

By John Krueger, Chair of the LCBP Heritage Area Program Advisory Committee.

Henry Brooks Adams’s life and work did not have direct ties to Lake Champlain, but it traced the early political and social forces of a nation in whose making the Champlain Valley played a critical role. Lake Champlain and the natural and cultural landscapes that surround it would, of course, go on to shape and be shaped by the arc of this nation’s history. And so Henry’s work is more relevant to this place than might first be apparent.

As it happens, Henry’s work also inspired a young historian who would go on to ruminate about the history of the Champlain Valley in a blog whose title and premise is based on his writings. Because of his influence and the fact that all but the most dedicated historians will be unfamiliar with him, it’s worth the time to dedicate an entry in this journal to this remarkable historian and social critic.

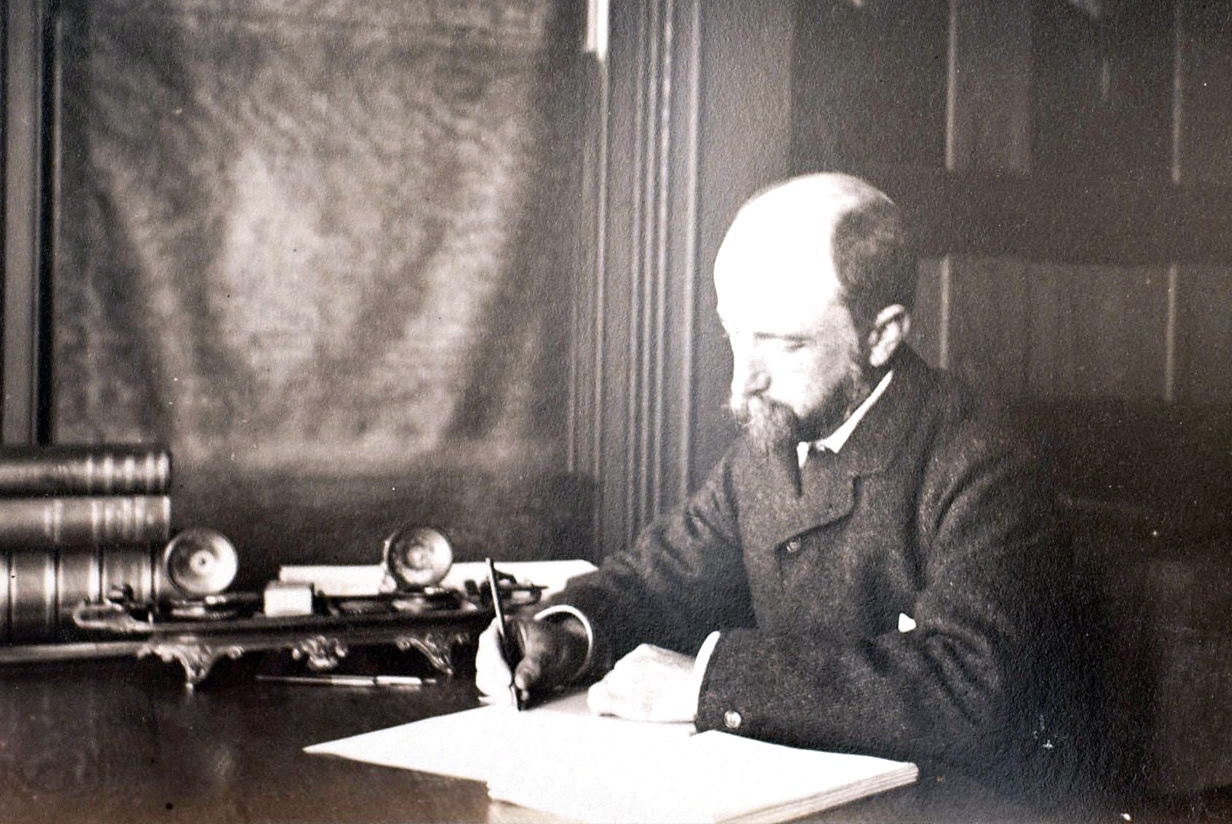

Henry Brooks Adams at work at home in Washington, D.C. in 1883. Photo by Marian Hooper Adams.

By the time of Henry Brooks Adams’s birth in his parents’ home at 57 Mount Vernon Street, on the summit of Beacon Hill in Boston, on February 16, 1838, the Adams family had become a political dynasty.

Henry’s great-grandfather, John Adams, helped write the Declaration of Independence and served as the second President of the United States. John Quincy Adams, Henry’s grandfather, was responsible for the foreign policy pronouncement known as the Monroe Doctrine and served as the sixth President. Charles Francis Adams, Henry’s father, served in the House of Representatives and achieved distinction as Lincoln’s Minister to Great Britain (the third Adams to hold that post) during the Civil War.

Henry attended Harvard College like his great-grandfather, grandfather, father, and older brother before him. While enjoying a grand tour of Europe following graduation—the first member of his family to do so—he wrote a letter to his brother Charles describing his future career plans: “Our house needs a historian in this generation and I feel strongly tempted by the quiet and sunny prospect.”

When Lincoln appointed Charles Francis as Minister to Great Britain in 1861, Henry accompanied him to London as his secretary. Returning to Washington after the Civil War, Henry became a freelance journalist. In September of 1870 thirty-two-year-old Henry Adams changed his mind, left Washington, and assumed the very regular duties of an assistant professor at Harvard. Hired as a teacher of medieval history, Professor Adams agreed to a five-year contract that paid $2,000 a year for nine lectures a week. Besides working intensively at medieval studies, the new instructor took over editorship of the North American Review, recruited writers Henry James and Francis Parkman, and turned that journal into an important instrument of social and political reform.

Henry also found time to enter society. By March 1872 he and Marian Hooper, known to her friends as Clover, were engaged. Married at the end of June, the new couple went abroad for a honeymoon year. Returning to Boston in the summer of 1873, they set up a household at 91 Marlborough Street, not far from 114 Beacon Street, the home of Clover’s father, Dr. Robert Hooper.

Henry Brooks Adams, 1883. Photo by Marian Hooper Adams.

In his teaching, Henry Adams moved from medieval to American colonial to early national history. His work was shaped by his desire to write scientific history based on the extensive and impartial use of primary sources with an emphasis on the development of broad concepts. Adams shifted his attention to the study of American history shortly before leaving Harvard to settle in Washington as an independent scholar and writer.

Adams’s historical masterpiece, History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, an ambitious narrative account of America during the years 1801-1817, was published in nine volumes between 1889 and 1891. A terrible tragedy struck while Adams was working on his History. Dr. Hooper died on April 13, 1885. Clover’s grief for her father was stronger than her love for her husband. Deeply depressed, on December 6, 1885, she went quietly upstairs in their house and poisoned herself with potassium cyanide, one of her photographic chemicals. Adams never truly recovered from this blow.

Henry Adams looked upon the dawn of the twentieth century with grim apprehension. “I am a pessimist – dark and deep – who always expects the worst, and is never surprised when it comes,” he reminded his closest female friend Elizabeth Cameron. “My country in 1900 is something totally different from my own country of 1860. I am wholly a stranger in it,” he confessed in the spring of 1900. “Neither I, nor anyone else, understands it. The turning of a nebula into a star may somewhat resemble the change. All I can see it that it is one of compression, concentration, and consequent development of terrific energy, represented not by souls, but by coal and iron and steam. What I cannot see is the last term of the equation.” Adams marveled at the dynamos he saw at the Chicago (1893) and Paris (1900) world fairs. He regarded electricity as almost supernatural: an “energy like that of the Cross.”

“It is a new century,” Adams exclaimed to his best friend, John Hay, from Paris on November 7, 1900, “and what we used to call electricity is its God. I can already see that the scientific theories and laws of our generation will, to the next, appear as antiquated as the Ptolemaic system, and that the fellow who gets to 1950 will wish he hadn’t.” His eightieth birthday gave him the sensation of having crossed a chasm in time. A few weeks later he retired after dinner at home at 1603 H Street and died in his sleep before morning on Wednesday, March 27, 1918.

Henry mused in his Pulitzer Prize-winning autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams, “A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.” He may have been uneasy with the tangled skein of American history at the dawn of the twentieth century—a history in which wires and fiber-optics might replace threads and yarn—but in this observation he affirms that while the world may look very different, history and the historian’s legacy as its interpreter will endure, and the tapestry he weaves will live and grow, based on all that came before.

Henry Adams could have been speaking to me, one of those fellows born in 1950. Growing up in the former Dutch frontier settlement of Schenectady, I spent each summer at Lake George. In May 1970, following my sophomore year at Boston University, I was hired by Jane Lape, then the curator at Fort Ticonderoga, to give guided tours. That first summer at the fort was a transformative experience. I have been an advocate for the region and its history ever since. Professor Catharine Newbold first introduced me to Henry Adams when I was a Ph.D. candidate at SUNY Albany in the mid-1970s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s I offered courses at the University of Vermont exploring and discussing Henry Adams and the other members of his fascinating family. Adams clearly believed that a sense of history provides our closest points of contact with the men and women of the past. Knowing your history fosters a pride of place. My place is Lake Champlain.[1]

[1] If you are interested in learning more about Henry and his friends please consider the following sources, all highly recommended: Paul C. Nagel, Descent From Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1983); Patricia O’Toole, The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and Friends, 1880-1918 (New York, NY: Clarkson Potter, 1990); Ernest Samuels, Henry Adams (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989); J. C. Levenson, Ernest Samuels, Charles Vandersee, and Viola Hopkins Winner, editors, The Letters of Henry Adams (6 volumes, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982-1988); Henry Adams, History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (2 volumes, New York, NY: Library of America, 1986); Henry Adams, Novels: Mount Saint Michel and The Education (New York, NY: Library of America, 1983); and Gore Vidal, Empire (New York, NY: Random House, 1987).