Threads of History

How the “brainiest woman in the United States” saved John Brown’s Farm

By John Krueger, Chair of the LCBP Heritage Area Program Advisory Committee

During her lifetime, the New York World described Kate Field as the “brainiest woman in the United States.”

Courtesy Boston Public Library.

Born in St. Louis in 1838 (the same year as Henry Adams), she was the daughter of two well-known actors. Kate was sent east in 1855 to live with her Aunt Cordelia and her millionaire husband, Milton Sanford, in Massachusetts. Aunt Corda and Uncle Milt supported Kate financially and took her to Paris, Rome, and Florence, where her charm and intelligence enabled her to flourish in a distinguished artistic and literary crowd, which included Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Anthony Trollope.

Kate would soon find success writing, sending articles to several American newspapers. Over the course of her career, she served as the Florence correspondent of the Boston Courier, the Newport correspondent of the Boston Post, the New York correspondent of the Chicago Tribune, and the London correspondent of the New York Herald, covering literature, theater performances, and exhibitions, as well as many other subjects.

Kate Field not only reported the news but made news herself. Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Alexander Graham Bell were among her professional acquaintances, and she first gained national attention for her reports on the 1867-68 American reading tour of Dickens, then the world’s most famous author. Henry James, a friend of both Kate and Henry Adams, modeled the character of journalist Henrietta Stackpole in his novel, The Portrait of a Lady, on Kate.

Newspaper and magazine writing brought recognition, but lecturing was one of the few lucrative careers available to women during the Gilded Age. Kate masterfully embraced the podium to promote social reforms and to increase her salary, declaring to her parents’ former stage manager, “I’ve gone into the Lyceum because it pays better than anything else, and I am tired of grubbing along.”[1]

At age thirty, she debuted on March 31, 1869, before a crowded house at Chickering Hall in Boston, presenting “Women in the Lyceum.” William Lloyd Garrison, the retired abolitionist editor, told his friends that “it was worth an admission fee just to see Kate Field on the platform, as she made so lovely a picture.” The New York Metropolitan Magazine declared, “It is veritably an intellectual feast to listen to the wit, humor and eloquence of this woman on the lyceum platform.” Kate eventually developed seven lectures that she delivered weekly, sometimes even more often, over a twenty-five-year period in cities such as Boston, New York, Washington, Chicago, and San Francisco, as well as in towns such as Weeping Water, Nebraska and Paw Paw, Michigan.[2]

Kate continued to write all the while, and the climax of her career came with the production of a weekly newspaper, Kate Fields’s Washington, a successful venture in which she wrote most of the articles herself. Following her death from pneumonia in Honolulu in 1896, the New York Tribune eulogized Kate as “one of the best-known women in America.” Her obituary in the New York Times described her as “one of the most versatile of her sex in this country,” while the Chicago Tribune speculated that she was “perhaps the most unique woman that the present century has produced.” Well-known and celebrated during her lifetime, Kate Field has been largely ignored by history.[3]

“Interesting lady,” you say, “but what does she have to do with the region encompassed by the Champlain Valley National Heritage Partnership?” Let me explain.

Inspired by William Murray’s just-published (April 1869) Adventures in the Wilderness, Kate spent the last three weeks of July 1869 in the Adirondacks, part of that time as Murray’s guest. According to the well-known orator Wendell Phillips, Murray’s wildly successful book “kindled a thousand campfires and taught a thousand pens how to write of nature.” Kate’s was one of those pens.[4]

When folks learned that Kate, with her mother and two other ladies, had plans to put Murray’s philosophy into actual practice, they offered no words of encouragement. “Four women! Order four coffins and take them with you” advised her critics. Kate followed Murray’s advice and camped out in the woods. “To come into the Wilderness and not camp out would be to me as unnatural as to bathe in a diver’s water-proof suit,” she remarked in the New York Tribune.

Kate described her experience: “The luxury of feeling that for one month out of twelve you can be a rough, stupid, good-natured, selfish animal, with no more regard for the sins and woes of humanity than have the birds of the air and the beasts of the field!” She fended off “black flies, musketoes, and midges” and gained fourteen pounds. Kate firmly believed that the Adirondack Mountains “were intended by Nature to be the Eastern pleasure-ground of the United States.” She submitted an essay based on her Adirondack adventures to The Atlantic Almanac, where it appeared in November 1870.[5]

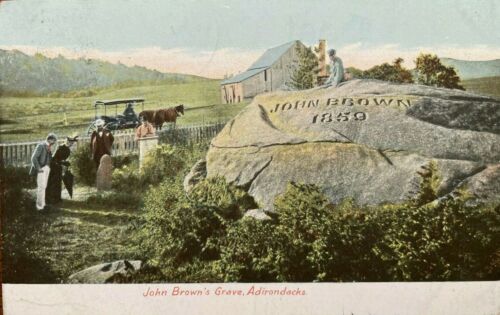

Before leaving the North Country Kate made a pilgrimage to North Elba, near Lake Placid, to visit the grave of the abolitionist John Brown. To her surprise, she discovered that the home, gravesite, and surrounding lands were about to go up for sale. “For sale with the bones of John Brown lying there!” she wrote. “I want the farm to be held as sacred ground, as proof that even in the nineteenth century there is such a thing as poetic justice.” Kate set out to purchase the property, contributing a hundred dollars and convincing nineteen others to do the same to successfully acquire the 244-acre parcel.[6]

Photo: Seneca Ray Stoddard

The Chicago Tribune published a lengthy review of Kate’s second lecture, “Among the Adirondacks.” The Tribune described how Kate held up the mirror of nature and held her listeners entranced. “Following her scampering feet,” the account reported, the “willing audience passed over green field, crossed babbling brooks, or rapid torrents, ascended mountains…slept under the dome of the midnight sky and did a hundred other things they never dreamed of doing before.”

She concluded with a tribute to the memory of John Brown. Standing beside his grave, “picking roses and buttercups that sprang from the giant’s heart,” Kate contemplated Brown’s life and legacy. “I saw him turn to the stouter, sterner mind and muscle of his own sons, reared to look God and nature in the face, he is still clinging to the Adirondacks, as if from them came inspiration,” she declared, “The moral of the Adirondacks is freedom!”

Friends advised Kate to delete the discussion of Brown from her talk, warning her that, “You will ruin yourself as a lecturer if you insist on eulogizing John Brown.” Kate had faced similar resistance in 1860 that would set her writing career in motion. While still in Florence, she publicly stated her belief that slavery was a curse and that John Brown was a hero. Her benefactor, Uncle Milt, a Southern sympathizer and owner/breeder of Thoroughbred racehorses who would accumulate a second fortune selling blankets to the Union Army, demanded that Kate retract her statement, or he would halt her allowance and disinherit her. Kate refused to back down, and it was then that she set out to make her own living as a journalist.[7]

She would not be deterred all those years later, and in 1896, Kate convinced the group that had purchased the John Brown farm to transfer ownership to New York State on the condition that it be used “for the purpose of a public park or reservation forever.” An official ceremony attended by hundreds of people was held at the farm on July 21. Kate died before the official transfer took place. Her ashes were eventually buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts between the graves of her parents.

The Essex County Republican acknowledged Kate Field’s impact on the Adirondacks, editorializing: “Of all public characters who are upon the platform today, Miss Kate Field should be foremost in the hearts of the citizens of Essex County, for she was among the first to agitate the question of the preservation of the forests of the Adirondacks.” Speaking as an Essex County resident living forty-one miles from John Brown’s farm, I applaud Kate Field’s pioneering advocacy of conservation and historic preservation.

[1] Kate Field to Noah Miller, July 3, 1869, in Carolyn J. Moss, editor, Kate Field: Selected Letters (Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996), 48.

[2] Moss, editor, Kate Field: Selected Letters, xxiii, xxviii; Field to Miller, July 3, 1869, Moss, Kate Field, 48.

[3] Kate Field has been the subject of only two biographies, written more than a hundred years apart: Lilian Whiting’s, Kate Field: A Record (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1899) and Gary Scharnhorst’s, Kate Field: The Many Lives of a Nineteenth-Century American Journalist (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2008). Whiting was Kate’s literary executor and apparently destroyed many of Kate’s letters and diaries after completing her biography. Sandra Weber’s, “A Babe in the Woods: Kate Field And Adirondack Preservation,” Adirondack Almanack, March 29, 2014, provides an interesting and well-written account.

[4] For more on “Adirondack” Murray, see https://champlainvalleynhp.org/2021/12/adventures-in-the-adirondack-wilderness/

[5] Kate Field, “In and Out of the Woods,” in Holmes, Oliver Wendell and Mitchell, Donald G. editors. The Atlantic Almanac for 1870 (Boston, MA: Ticknor and Fields, 1870), 48-52. Kate’s essay is also available at:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015069468307&view=1up&seq=208&skin=2021

[6] The most detailed accounts of this episode may be found in Kate Field, “John Brown’s Grave and Farm,” Kate Field’s Washington, January 13, 1892; KF to William Claflin, September 7, 1869, Moss, Kate Field, 50; and Alfred L. Donaldson, A History of the Adirondacks (Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books, 1977) 2 volumes [first published New York, NY: Century Company, 1921], II, 3-22.

[7] Kate made her feelings known concerning slavery and John Brown in her interpretation of Elizabeth Barret Browning’s poem “A Curse for a Nation” (1860). Here’s an interesting Sub-Thread of History for those of you who read the notes: In the summer of 1868, following a day of racing at Saratoga, Milton Sanford hosted a now-famous dinner party at the fashionable Union Hotel at Saratoga Springs where it was suggested that the occasion be commemorated with the establishment of a Stakes race to be called the Dinner Party Stakes. All agreed that the race would be held in the fall of 1870 with a lucrative $15,000 purse. Oden Bowie, the governor of Maryland, attended and promised that if the race would be run in Maryland, he would see to it that a new racetrack would be built to host it. On October 25, 1870, a horse named Preakness owned by Milton Sanford won the inaugural Dinner Party Stakes. The Preakness Stakes, established at Pimlico Race Course in Baltimore in 1873, was named in honor of Sanford’s horse.